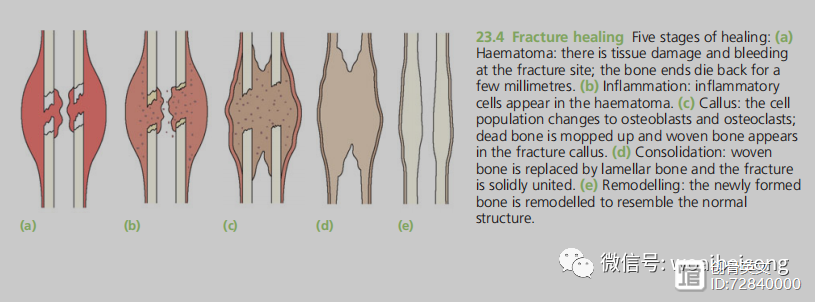

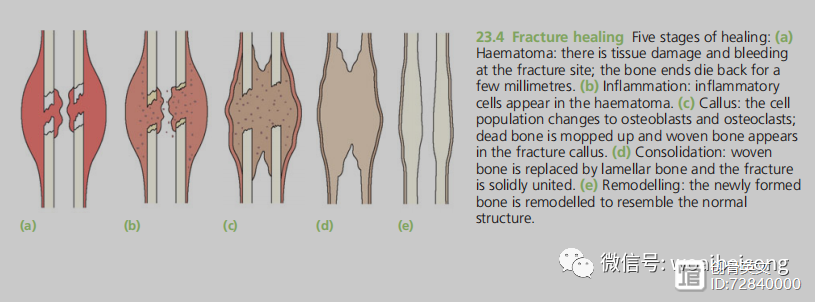

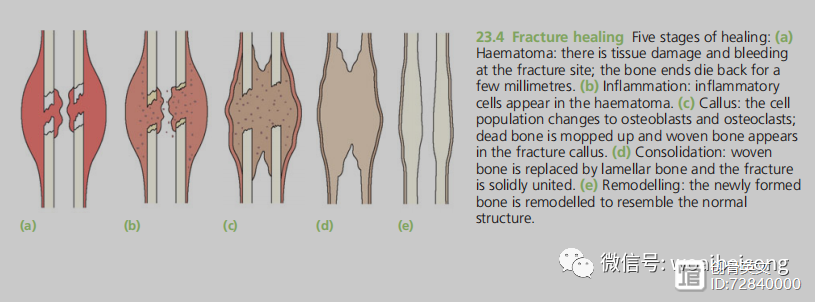

HEALING BY CALLUS

This is the 'natural’ form of healing in

tubular bones; in the absence of

rigid fixation,

it proceeds in five stages:

1.

Tissue destruction and

haematoma

formation

–

Vessels are torn

and a haematoma forms around and within the fracture. Bone at the fracture surfaces,

deprived

of a blood supply, dies back for a

millimetre

or two.

2.

Inflammation and cellular proliferation

– Within 8 hours of the fracture there is an

acute inflammatory reaction

with

migration

of inflammatory cells and the initiation of

proliferation

and

differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells

from the periosteum, the

breached medullary canal

and the surrounding muscle. The fragment ends are surrounded by cellular tissue, which creates a

scaffold

across the fracture site.

A vast array of inflammatory mediators (cytokines and various growth factors) is involved.

The clotted haematoma is slowly absorbed and fine new capillaries grow into the area.

3.

Callus formation

– The differentiating stem cells provide

chrondrogenic

and

osteogenic cell

populations; given the right conditions – and this is usually the local biological and

biomechanical

environment – they will start forming bone and, in some cases, also

cartilage. The cell population now also includes

osteoclasts

(probably

derived from

the new blood vessels), which begin to

mop up

dead bone. The thick cellular mass, with its islands of

immature

bone and cartilage, forms the

callus or splint

on the

periosteal and endosteal surfaces.

As the immature fibre bone (or 'woven’ bone) becomes more

densely mineralized, movement at the fracture site decreases progressively and at about 4 weeks after injury the fracture 'unites’.

4.

Consolidation

– With continuing osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity the woven bone

is transformed intolamellar bone. The system is now rigid enough to allow osteoclasts to

burrow

through the debris at the fracture line, and close behind them.

Osteoblasts

fill in the remaining gaps between the fragments with new bone. This is a slow process and it may be several months before the bone is strong enough to carry normal loads.

5.

Remodelling

– The fracture has been bridged by

a cuff of

solid bone. Over a period of months, or even years, this crude 'weld’ is reshaped by a continuous process of

alternating bone resorption and formation.

Thicker lamellae are laid down where the stresses are high, unwanted buttresses are carved away and the medullary cavity is reformed.

Eventually, and especially in children, the bone

reassumes

something like its normal shape.

---from

《Apley’s System of Orthopaedics and Fractures》P690